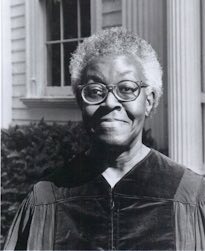

“I am interested in telling my particular truth as I have seen it.” Gwendolyn Brooks has seen her truth on the south side of Chicago, where her parents moved when she was less than one year old. An introverted, shy child, she grew up reading the Harvard classics and the Black poet Paul Lawrence Dunbar. She grew up writing with her first poem being published at 14 years old.

Graduating from Wilson Junior College the Depression, she could only find work as a domestic worker and as secretary to a spiritual advisor. Later, she became publicity director of the youth organization of the NAACP in Chicago. She continued writing and by the end of the early 1940’s her poetry was appearing in Harpers, Poetry and The Yale Review. In 1945, her first volume of poetry A Street in Bronzeville was published. “I wrote about what I saw and heard on the street,” she said of that book. In 1949, she published Annie Allen, a series of poems that traces a Black girl’s progress to womanhood. It was for this volume that she won the Pulitzer Prize in 1950.

In 1967, an established and respected poet, she attended a writer’s conference at Fisk University. There, she says, she rediscovered her Blackness. Her subsequent poetry broke new ground for her, reflecting the change that occurred at Fisk. The Mecca, a book-length poem about a mother searching for her lost child in a Chicago housing project, shows this new direction. This volume was nominated for the National Book Award for poetry. Her other work includes children’s books, an autobiography, and a collection of poetry about South Africa. Her work is collected in a single volume titled: BLACKS. She has been called a poet who has discovered the neglected miracles of everyday existence. For Brooks, it was all a matter of telling her truth.