Learn More about the Virtual Induction Series

Mary Church Terrell (1863 –1954)

Mary Church Terrell, born during the Civil War, was one of the most prominent activists of her era with a career that spanned well into the civil rights movements of the1950’s. Terrell was one of the first Black women to earn a college degree, in Classics at Oberlin College, and one of the first to earn an MA. She taught Latin at the M Street school— the first Black public high school in the nation—in Washington, DC. In 1896, she was the first Black woman in the United States appointed to the school board of a major city, serving the District of Columbia until 1906. She was a founding member and served as the first president of the National Association of Colored Women, was a charter member of both the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and the Colored Women’s League of Washington. She was a founding member of the National Association of College Women. A dedicated suffragist during her Oberlin years, she continued to be active within circles in the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).

Terrell believed in racial uplift and equal opportunity, actively campaigning for women’s and Black women’s suffrage. She picketed the Wilson White House with members of the National Woman’s Party. As one of the few Black women allowed to attend NAWSA meetings, Terrell directly spoke out about the racism and injustices experienced within the Black community. Her association with NAWSA inspired Terrell to create a formal organized group for Black women in America to address issues of lynching, Black disenfranchisement, and education reform. Terrell wrote abundantly about Black female empowerment, including an autobiography, A Colored Woman in a White World. At the age of 80, she continued to participate in picket lines, protesting the segregation of restaurants and theaters. During her senior years, Terrell successfully persuaded the local chapter of the American Association of University Women to admit Black members. She lived to see the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education, holding unconstitutional the racial segregation of public schools. Terrell died two months later at the age of 90, on July 24, 1954.

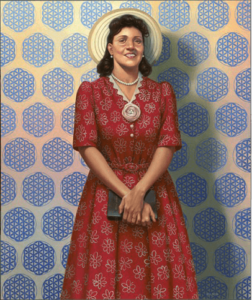

Henrietta Lacks (1920 – 1951)

Henrietta Lacks (1920 – 1951)

Henrietta Lacks is best recognized for her immortal HeLa cells, which have been used in research that led to the development of the Polio vaccine, chemotherapy, and contributed to Parkinson’s research. In 1951, Henrietta Lacks went to Johns Hopkins Hospital for treatment for an unknown illness, a “knot” in her abdomen. After several hospital visits, she died of cervical cancer on October 4, 1951. Lacks died at the age of 31 years old, and left behind her husband and five children. After her death, a lab attendant discovered that a swab of Lacks’ cancer cells reproduced at an extremely fast rate. This was extraordinary because while most cancerous cells died within a few days, Lacks’ cells doubled every 24 hours. Research led by Dr. George Gey, marked the first instance of continuous growth of human cells outside the body. Lack’s cells were the first recorded example of cells that divided multiple times without dying, which is why her cells were coined, “immortal.” The HeLa (named for the first of letters of her first and last names) cells would go on to transform modern medicine. To date, the easy-to-grow HeLa cells have been used in more than 76,000 studies.

Henrietta Lack’s case began a conversation about medical ethics, particularly the morality of using someone’s cells without their consent. It took about twenty-five years for the Lacks family to receive any knowledge about the contribution their beloved wife and mother was making to modern science. The Lacks family still has not received compensations for the contribution Henrietta Lacks made to modern science. Henrietta Lacks not only left a legacy of medical research, but also a legacy of policy regarding how doctors should ethically, and morally, handle biological specimens from humans.

Toni Morrison (1931 – 2019)

Toni Morrison, was a novelist, essayist, book editor, and college professor. Morrison broke barriers; she was the first Black woman to become senior fiction editor for Random House and the first Black woman to win a Nobel Prize in Literature.

In 1967, Morrison began at Random House, where she played a vital role in bringing Black literature into the mainstream. During this period Morrison began writing fiction informally. She recalled her parents instilling a great sense of heritage and language throughout her childhood, often telling traditional African-American folktales, ghost stories, and songs. These early influences are evident in her fiction novels, which focus on the vivid portrayals of the Black female experience. Her first novel, published in 1970, The Bluest Eye, was inspired by a short story about a Black girl who longed to have blue eyes. The critically acclaimed Song of Solomon brought her national attention and won the National Book Critics Circle Award. In 1988, Morrison won the Pulitzer Prize for Beloved. In 1998, Beloved was made into a film which was co-produced by 1994 Inductee Oprah Winfrey, who had spent ten years adapting it for the screen.

Morrison indelibly demonstrated that great literature is neither bound to be written by men nor exclusively by people of European descent. She fostered a new generation of Black writers, including poet Toni Cade Bambara, activist 2019 Inductee Angela Davis, and novelist Gayl Jones. She has been unapologetic about her focus on Black people’s experiences, and the power with which she has brought this focus has earned her the moniker, “The Conscience of America.”

Barbara Hillary (1931 – 2019)

Barbara Hillary had a successful career as a professional nurse and served as the Founder and Editor-in-Chief of the Peninsula Magazine, the first multiracial magazine published by a Black woman. She is most well known as being the first Black woman to have ever traveled to both the North and South Pole- both after the age of 75. After retiring, Hillary became fascinated with arctic travel, although she had an adventurous spirit instilled in her at a young age.

Hillary grew up impoverished in Harlem, New York City, and spent much of her time reading, her favorite book being the adventure novel, Robinson Crusoe. She recalled, “there was no such thing as mental poverty in our home.” When Hillary learned that no Black woman had reached the North Pole, she was determined to become the first one to do so. She found new challenges by learning to snowmobile and dog sled in the United States and Canada. A polar expedition at the time cost around $20,000 and required her to ski, something she had never done before. Undeterred, Hillary sent letters to potential sponsors and took in donations, eventually raising over $25,000 to fund her expedition to the Arctic. To prepare for her journey, she took cross-country ski lessons and hired a personal trainer. On April 23, 2007, at the age of 75, she became one of the oldest people to set foot on the North Pole, and the first Black woman. Five years later, she became the first Black woman on record to stand on the South Pole at age 79, on January 6, 2011.

Inspired by her expeditions, Hillary took interest in the effects of climate change on the polar caps and became a fierce advocate for combating climate change. She began lecturing on the topic. Her activism took her to the Mongolian steppe to visit a community whose cultural traditions were at risk due to climate change. Hillary’s career as an inspirational speaker led her to being profiled by NBC News and CNN.com, and she gave speeches at various organizations such as the National Organization for Women (NOW).

Barbara Rose Johns Powell (1935 –1991)

Barbara Rose Johns Powell (1935 –1991)

Barbara Rose Johns Powell was a young, civil rights leader and pioneer. At the age of 16, Powell led a student strike, for equal education, at R.R. Moton High School in Farmville, Virginia.

After years of frustration with the inadequacies at her school, such as poor facilities, shabby equipment, and no science labs or gymnasium, Barbara took her concerns to a teacher, who dismissed her. Although initially discouraged, Barbara Rose Johns, used this moment as inspiration and created a plan. On April 23, 1951, she and her student council members went on strike. Johns gave a speech to all 450 students at the school, detailing their dissatisfaction, and revealed her plans for a student strike in protest. The students were inspired and marched with Johns Powell to the county courthouse to state their case.

Barbara Rose Johns’s planning and persistence garnered the support of NAACP lawyers who took up her case and the cause of more equitable conditions for Moton High School. After securing NAACP legal support, the Moton students filed Davis v. Prince Edward County, the largest and only student-initiated case. In 1954, this case became one of the five cases that the U.S. Supreme Court reviewed in Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision declaring “separate but equal” public schools unconstitutional.

For her part in the integration movement, Johns was threatened, and the KKK burned a cross in her school yard. Barbara Johns’ parents, fearing for her safety, sent her to Montgomery, Alabama, to live with her uncle, Vernon Johns, a civil rights pioneer. Her commitment to equitable education moved her to become a librarian. She served in this profession until her death in 1991. Some historians believe that Johns’s contributions to the Movement are frequently overlooked because of her young age. Her actions were extraordinary given her age and the era.

Aretha Franklin (1942 –2018)

Aretha Franklin was a singer, songwriter, pianist, actress, and civil rights activist. Her multi-octave vocal range moved millions of people around the world during an expansive career that spanned six decades. As a child, Franklin learned how to play piano by ear, and by the age of 12 her father, a prominent preacher, began managing her career. She accompanied him on the road as he traveled in his, “gospel caravan” tours where she performed at various churches. At the age of 16, Franklin went on tour with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and years later performed at his funeral. Once she turned 18, Franklin made the decision to transition from gospel to pop music and moved to New York. In 1960, she signed with Columbia records and released her first secular album, Aretha: With The Ray Bryant Combo. The album was a mix of diverse genres such as standards, vocal jazz, blues, doo-wop, and rhythm-and-blues. By the end of 1961, Franklin had her first international hit, “Rock-a-Bye Your Baby with a Dixie Melody,” and she was named the “new-star female vocalist” by DownBeat magazine.

Her career continued to skyrocket, as Aretha Franklin became a household name. By the end of the 1960s, Franklin had come to be known as the “Queen of Soul.” Many of Franklin’s songs, such as “Respect,” and “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman” became anthems of movements for social change. Throughout her life, Franklin was immersed and involved in the struggle for civil rights and women’s rights. She provided money for civil rights groups, at times covering payroll, and performed at many benefits and protests. Aretha Franklin was the first woman to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. She was awarded a Grammy Legend Award in 1991 and later awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1994. Franklin was a Kennedy Center Honoree, recipient of the National Medal of Arts, American Academy of Achievement’s Golden Plate Award, presented by Awards Council member and NWHF 2011 Inductee Coretta Scott King. Aretha Franklin’s music has been an inspiration for many artists, and her legacy is enduring.